We have always been baffled about "victimization". The teenage sexuality, child porn, irrational drug prohibition witch hunts are based on victimization theories. These victimization theories are so outlandish, they make the medieval "theory that witches cause hail storm" look like sound science.

First come our preconceived moral judgments. Then we find justifications and victims.

In deciding what other people shouldn’t do, people don’t necessarily start with some principle and go from there. It could have been that moral reasoning was not unlike mathematics-start with a few axioms, and see what follows from them. If people did that, then their moral reasoning would be consistent. Everything follows from the assumptions. But they don’t, or at least, not always.2

All quotes from:

Why Everyone (Else) Is a Hypocrite: Evolution and the Modular Mind * (Robert Kurzban)

(p. 188 ff | Kindle Loc. 2322-64)

- first comes a moral judgment, like "promiscuity is bad", "creeps who possess child porn photos need to be punished", "having sex with adolescents is disgusting" (or "smoking marijuana is bad"). Some of these judgments stem from evolutionary mental modules hard-wired into our minds. Or course, our culture plays a role here too, especially in how we justify our moralistic feelings

- After the fact, after we already decided that sex with nubile adolescent women is heinous, our mental "press secretary" has to come up with socially acceptable justifications for punishing people for apparently victimless crime. So our mind is made in ways that it finds justifications for our moral judgments. It comes up with logical reasons. It invents victims that need to be protected

Tiger Woods, hypocrisy, moral condemnation of promiscuity: where are the victims of a billionaire’s secret dalliances? Tiger Woods: why can’t he have open marriage and have fun?

For things like sex-which many people want to do-people are very happy to apply moral principles. They think that decisions about what is right and what is wrong, what should be permitted and what should be banned and punished, should derive from principles. In this case, the principle is freedom or liberty: People ought to be allowed to do what they want as long as it doesn’t hurt others.

[…] But that’s not the way people make all moral judgments, and by moral judgments here I don’t mean how people decide what they themselves should do-what their conscience tells them. I mean how people decide what other people ought not to do, what other people should be punished for.1 […]

People seem to judge acts first, and search for justifications and victims afterwards, which strongly suggests that one coherent set of principles isn’t driving moral judgments.

Human-Stupidity suspects that our modern manipulative language distortion stems from such attempts to justify moralistic interference.

Human-Stupidity suspects that our modern manipulative language distortion stems from such attempts to justify moralistic interference.

Who are you calling a victim?

One way you can tell people make their moral judgments based on nonconscious intuitions is that they can’t explain their own moral judgments, as we’ve seen with Jon Haidt’s work on "moral dumbfounding." People will say that incest is wrong without being able to give any justification for it. Incest is just wrong.

Kurzban is a scientist. He will not argue if incest is right or wrong, He is analyzing the functioning of the human mind. He notices that people are totally convinced of the immorality of incestual relationships and can not explain why it is immoral. Even the incestual couple is adult and infertile, it still is wrong.

Many modules seem to cause people to find certain things wrong and to work to prevent others from doing them.Often, people can’t actually tell you the real reason behind those judgments, any more than they can tell you why they think they’re among the best drivers in the country.

Our moral convictions make us find logical explanations and victims at all cost.

We’ve been studying moral intuitions in my lab as well. Peter DeScioli, Skye Gilbert, and I have done some work looking not at moral justifications, but rather intuitions about victimhood. You might think that when people make moral judgments, they first determine if there’s anyone who is a victim-anyone made worse off by the act in question-and use that when they’re making their moral judgment. But we think that for at least some offenses, it’s the other way around.

Researchers got rid of all potential victims from scenarios. If there absolutely can not be a victim, we find a victim anyway

We presented people with a set of "victimless" offenses-things like urinating on a tombstone, burning a flag, cloning a human being, and so on-and asked our subjects if the act was wrong or not. After that, we asked if anyone was harmed by the action. What we found was that almost anyone who said an act was wrong also indicated a victim. But the victims included entities like "humanity," "society," "the American people," "friends of the deceased," "the clone," and so on.

Now, of course it’s possible to argue that somehow these entities really are worse off as a result of the actions. So in a follow-up, we changed the scenarios to get rid of these potential victims. We had a story in which someone urinated on the tombstone of someone with no living family or friends, or a scientist cloned a human being, but the clone was never alive, so couldn’t ever have suffered, felt pain, or worried that she was a clone.

Doesn’t seem to matter. People still judged the acts wrong, and, when they did, they searched for a victim. If the clone wasn’t ever alive, fine, the clone wasn’t the victim: the scientist (somehow) was. If the dead person had no family or friends, "society" was worse off.

People seem to judge acts first, and search for justifications and victims afterwards, which strongly suggests that one coherent set of principles isn’t driving moral judgments.

Here is the explanation for the amazing theories of victimization with child porn, about consensual sex with adolescents being exactly the same as violently raping the same adolescent. These theories actually have become law and terrorize men with long jail sentences.

OBS: Dr. Kurzban is not responsible for conclusions Human-Stupidity draws from his work.

Immoral judgments aren’t driven by a set of consciously accessible general principles that are applied to particular cases.

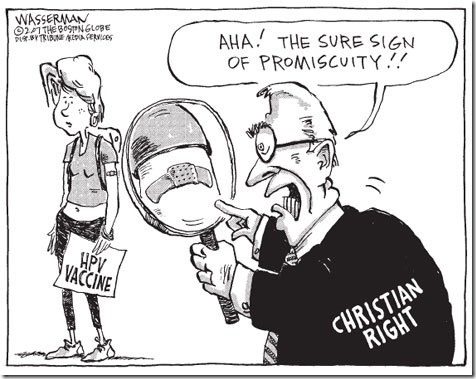

Evolutionary psychologist Robert Kurzban explains

how we gain reproductive advantage by moral condemnation of promiscuity and interfering in other people’s sex life

Wait, there is more! This article continues! Continue reading “To justify our moral judgments, we invent victims even if there are none” »

To justify our moral judgments, we invent victims even if there ar…

» continues here »